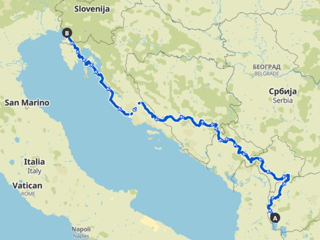

Ohrid – Tetovo (North Macedonia) – Prizren – Peja (Kosovo) – Čakor Pass – Plav – Durmitor N.P. (Montenegro) – Konjic – Blidinje N.P. (Bosnia-Herzegovina) – Sinj – Knin … Šibenik – Zadar – Pag – Rab – Cres – Roč (Croatia) – Trieste (Italy)

1,444 km cycled

This is the “Starter”- video

Let’s face it! We are dedicated fans of the Balkans. So when we were given a half kilo of tourist information about Via Dinarica during our ride across Bosnia-Hercegovina in autumn 2019, we gladly accepted. Originally a hiking trail stretching from Slovenia all the way to North Macedonia, Via Dinarica had great appeal, but of course we wanted to follow the route “a la carte” on our bicycles.

Because it turned out to be a rather packed program across ex-Yugoslavia and touching on seven countries, we’ve divided it in true a-la-carte fashion into starter (Ohrid to Plav), main course (Plav to Knin) and dessert (Šibenik to Trieste).

Ohrid (North Macedonia) to Plav (Montenegro)

Ohrid, Macedonia was a perfect starting point thanks to its convenient air connection from Zurich and scenic lake location, which we discovered on our Albania trip a number of years ago. It would also allow us an extended crossing of Kosovo and a spectacular exit over a hiker/biker border at the Čakor Pass.

Ohrid didn’t disappoint, even if we had to lug our bikes up four flights of stairs to reach the apartment, which we had booked online. Still, we got a swim in the lake, a few great meals and a folklore festival thrown in for good measure. Darina even got a summer haircut as temperatures hovered around the 30°C mark.

We left the same way as the last time along the Black Drin River to Debar, before turning to Mavrovo N.P. instead of crossing into Albania. Two beautifully scenic rides followed, and we crossed our first pass into Gostivar.

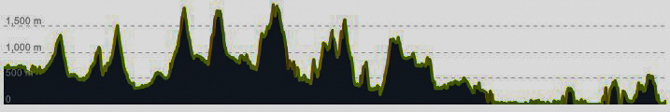

Kurt was responsible for planning this trip and working out a route that would maximise on sights and scenery. Darina left it in his capable hands and downloaded the GPS tracks to her little bike computer without giving it any thought. It wasn’t until she was climbing a steep stretch in 34°C heat along the Black Drin that she discovered a further 90 climbs lay ahead. Actually, by the time we hit Triest, we had cycled 22,000 altitude metres! And this is what Kurt calls holidays!

From there to Tetovo, German was our mode of communication. Because of high unemployment since the breakup of Yugoslavia, scores of locals have gone in search of work to Germany, Austria and Switzerland. A typical village would have 400 houses with only 200 year-round inhabitants. It all comes to life in summer when the expats roll in with their families; local festivals are the order of the day. Vranica village was a bit of an exception in that the 2,000 that left went to Detroit, USA.

Just after the quiet border into Kosovo, we had another very pleasant climb through alpine forests and meadows, and past a skiing station and a few waterfalls up to Prevallë. Sadly, the picnic spots were easy to spot by the amount of rubbish strewn around. It was just 20km down into Prizren, the last few kms through a beautiful gorge with a monastery at the bottom and a few defensive towers on top.

Prizren, the former capital of the Kosovan province during Yugoslav times, is now the cultural centre with Prishtinë taking the lead. It’s a delightful old town along a river, complete with mosques and churches from the last few centuries. The streets are lined with cafes, bars and eateries and there is never a dull moment.

Now, it was time for Kurt to go to the barber for a shave, haircut, and head massage all in one. He can highly recommend going into a shop where communication is more manual than verbal 😉

We opted for a daytrip by bus to Pristina to explore the big smoke. Kosovo, the youngest (and still disputed) country in Europe certainly has a story to tell; the numerous monuments in Pristina are testament to the difficult journey that led to independence from Serbia. The Newborn monument was unveiled on Liberation Day: Feb 17, 2008.

One of the more poignant monuments is the Heroinat (female heroes), dedicated to the victims of sexual violence during the war. It depicts the face of an Albanian woman and comprises 20,000 brass medals representing the number of women thought to have been raped between 1998 and 1999.

St. (Mother) Teresa, an Albanian born in present day North Macedonia, is held in high esteem and has a monument, church and boulevard named after her. Bill Clinton is also commemorated in recognition for his role in the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999 that subsequently led to Kosovo’s independence.

The creative National Library was built in 1982 and designed by a Croatian architect, encorporating Byzantine and Islamic forms. It contains 99 domes of varying sizes and is covered by a honeycomb-type metal mesh, which some locals reckon resembles scaffolding! While we loved the building, it has been listed by The Virtual Tourist as one of the ugliest buildings in the world!

Another peculiarity in Pristina was the dilemma we were faced with when we went to the toilet (see below)!

As temperatures got higher than pleasant, we had a very early start out of Prizren, hoping to arrive in Peja by lunchtime. What we didn’t factor into the equation was the number of times we would be stopped by locals for a chat or invited for coffee/cold drinks/icecream. One man even crossed a 6-lane street to hand us a bottle of cold water! The hospitality in this neck of the woods is exceptional and reminiscent of what we experienced in Albania.

In Kosovo, 90% of the inhabitants are ethnic Albanian; ethnic Serbs are in the minority. Beside every Kosovan flag, it’s not unusual to see an Albanian or Serbian flag to mark the ethnicity of the area. In Albanian villages, euros are the local currency, while in Serbian villages the Serbian Dinar is the norm. On top of that, Albanian or Serbian is the language used depending on ethnicity; the segregated schools do not share the same curriculum. While we were welcomed by both sides, we did notice that if we spoke the “wrong” language, we were either corrected or got a cool reception!

With this political undercurrent, it wasn’t surprising that when we saw several police cars and military jeeps, along with numerous TV cameras and reporters outside the hospital in Decan, we jumped to political conclusions! As it turned out, the area had just declared a state of emergency after more than 1,500 people had sought medical attention with food poisoning symptoms, thought to have stemmed from the local water supply. The president sped into town for a press conference and immediately called for an investigation. A few days later two Serbian nationals who had been spotted in the town were arrested for questioning. By the time we left the country, tension was mounting, and the mystery was still unsolved.

Peja is famous for its medieval orthodox monastery at the entrance to the Rugova canyon. Like a Serbian exclave in this ethnic-Albanian area, it is guarded by watchtowers on the outer wall and a passport is required to visit. The churches (4 in 1) are adorned with superb murals dating back to the 13th century and the monastery has earned a well-deserved place on the list of UNESCO world heritage sites.

To cycle over the Čakor Pass into Montenegro is possible, but it’s advisable to get a permit from Kosovo and Montenegro in advance, as the border is not manned. Thanks to the German cycling website “Quäldich,” we found a link to Zbulo, an organization that arrange these permits for their hiking tours and happily oblige cyclists. The permit application should be made two weeks ahead of the crossing, but a two-day leeway is given with weather and exhaustion as acceptable excuses for any delay!

Armed with said permits, we headed off into the Rugova Canyon in the Accursed Mountain range. It’s quite an impressive road, hacked into sheer cliffs; it includes numerous hairpin bends (even in tunnels), until it opens into beautiful alpine meadows. The border itself is marked by three anti-tank blocks and a hiking signpost. Another 700 altitude meters on a paved road brought us up to the actual pass. It was a splendid ride with not a car in sight. Absolutely blissful cycling!

Down in Plav, Montenegro, we registered with the border police, Darina enjoyed a dip in the freezing cold lake, and we put up the tent before going for a well-deserved meal to conclude the starter.

Plav (Montenegro) to Knin (Croatia)

From Plav, we had a short downhill stretch to Andrijevica, and then the fun started! Up a valley past small farming communities for a while and then serpentines through shady forest up to a pass of 1,570 masl. On the following downhill we had impressive views of mountains reaching almost 2,500 masl.

On reaching Kolašin, the approaching wet front convinced us of the merits of a rest day. That was easily filled exploring the town, chatting friendly locals and with a short hike to a traditional restaurant serving Kaçamak, a local speciality.

Kaçamak, a mixture of cooked cornmeal, potatoes, cream cheese and sour cream could be called soul food if your soul is more into quantity. They say that if you don’t finish your plate your partner will leave you. Struggling with the 900g of stodgy mass, we came up with the brainwave to beat tradition and leave together!

Following the Tara Gorge to the famous Ɖurđevića Bridge, we arrived just in time to find a room & shelter before a serious downpour. A short day up to Žabljak, the main town servicing Durmitor N.P., left us plenty of time to hike around the beautiful Black Lake.

The Ɖurđevića or Tara Bridge was the largest concrete arched vehicular bridge in Europe when completed in 1939. Just three years later, as German troops congegrated in Žabljak during World War ll, the local partisans decided the best way to slow their advance was to blow up the bridge. One of the engineers involved in the building of the bridge was called on to do the honours and when captured by the Germans he was executed on the remains of his wonderful creation. It was rebuilt in 1946.

Durmitor N.P. is where Patagonia meets the Ring of Kerry and was definitely one of our highlights on this trip. The paved road is an easy cycle through stunning scenery and the 1,900m pass is very doable.

Totally high on landscape, we reached the downhill to the turquoise Piva Lake: another spectacular road hacked into the cliff with endless tunnels and hairpin bends. By late afternoon we had reached our campground at a rafting site overlooking the Bosnia and Herzegovina border. What a day!

Across the border, we continued to follow the Tara River as far as Brod. By the time we hit the Bistrica Gorge, we had become somewhat blasé about gorges. Had we known what was ahead, we might have appreciated it a little more! Steep dirt tracks and rough gravel routes followed up and down side valleys to Boračko Lake, and there was another insane climb and a half before tumbling down to the Neretva River again.

By then, Kurt’s back brakes were literally screeching. Presuming that brake shoes were common all over Europe, we have never bothered carrying spares. Well, Konjic may be a lovely town, but disk brakes were unheard of. So we spent the afternoon visiting Tito’s bunker!

Secretly built in the exact centre of Yugoslavia to protect then President Tito and 350 of his inner circle in the event of a nuclear war, this extensive control room and shelter is almost as grandiose as Hoxha’s in Tirana, Albania. The real size is still unknown since it is now in the hands of the Bosnia and Herzegovina army; access is only to the ground floor and Tito’s room upstairs. In any case, 26 years of construction costing 5 billion dollars in 1979 seems like an outlandish investment in the name of power and fear.

Following the Neretva River to Jablanica was easy. Here we crossed our Bosnia & Hercegovina route from autumn 2019 before heading up a side valley to Blidinje N.P. This was our last big climb of over 1,200 altitude meters. By the time we reached the pass onto the “altiplano,” we were knackered.

The plain is famous for its stećci; big medieval carved tombstones. One has a text telling passers-by to leave them in peace, because I was like you, and you’ll soon be like me! We examined a number of them right next to the road and contemplated the fact that for us it’s not yet a dead end!

Past Lake Blidinje, we cycled down to Tomislavgrad and on to the serene Lake Buško, where we camped on the sandy beach with not a soul in sight. Heaven on earth!

Having crossed the Croatian border, lovely roads led us to the town of Sinj where we had the opportunity to watch a training session for their big annual Alka tournament. Riders in full gallop try to spear a small hanging ring with their lance, gaining points depending on where they hit it. Fascinating viewing.

On the way to Knin we passed Mount Dinara, the peak that gave its name to the Dinaric Alps and hiking route that inspired this trip. Although unassuming at first sight, it did earn our appreciation as we got closer and could admire Croatia’s highest mountain standing at 1,831 masl.

Another small and very dry gorge brought us to Knin, the hottest place in Croatia, with temperatures approaching 37°C. The town is renowned for its recent violent history. Predominantly a Serbian town by the time the war broke out in 1991, it wasn’t taken by Croatian forces until 1995.

Having seen Mount Dinara, it was the perfect time to move on to dessert. Since there are three Via Dinarica routes, we decided to align our tour from here on to the blue one along the coast, just as “a la carte” as we did before with the white route.

Here is the “Main course”- video

Šibenik (Croatia) to Trieste (Italy)

To save a half day cycling in furnace-like heat, we jumped on a train to the historic town of Šibenik on the Dalmatian coast. We were ready for a rest. And the town was ready to host us. Coastal views, a delightful apartment and excellent dining made it for us.

Zadar is a low-key historical centre of the Dalmatian region and is listed by UNESCO for its city walls dating back to the 16th century. Its four bicycle shops all had brake pads but alas, none that were compatible with Kurt’s disk brake. Not what we wanted to discover, as by now his front brakes had started to grate.

The road to Pag was very busy, but the unique desolate landscape distracted us sufficiently.

Leaving Pag town, we discovered a lovely quiet coastal road with views of beautiful turquoise coves surrounded by pine trees, reminiscent of the Costa Brava. We thought we were in Heaven until the road ended abruptly thanks to a landslide, which probably accounted for the lack of traffic! Rather than going back, we scouted a short hike down the 10m drop and hauled bikes and luggage piece by piece down the steep dirt trail.

Ferries around here tend to moor at the steepest piece of land in sight, resulting in a lot of climbing and down hilling to get the roll on-roll off effect. Fortunately, on Rab, the traffic only lasted until the ferry was empty and then we had the road to ourselves. We found Rab (town and island) a lot more fertile and attractive than Pag and would include it in a future trip without hesitation.

Another ferry combo brought us via Krk to Cres, where we had another blast from the past; a spring trip some 12 years ago. The island is still lovely and relatively quiet, and we enjoyed the ride. Darina had blocked out any memory of those steep climbs in the north… or could it be that we were a whole lot fitter back then? And for old times’ sake, Istria greeted us with a 16% incline.

We got to see the smallest town on earth; a walled hamlet called Hum, and then a slightly bigger one called Roč, where we found a cute little back-garden campsite.

A last insane incline saw us to the Slovenian border. Horrendously high and hostile barbed-wire-topped fences, protecting central Europe from a possible surge of refugees, stretched as far as we could see. It seemed totally out of place in a region otherwise so hospitable and welcoming.

We spent all of two hours in Slovenia before crossing into Italy. With insider knowledge from our trip 12 years ago, we headed straight for Múggia to take the ferry into the centre of Trieste, cutting out the endless industrial suburbia.

The plan for our grand finale in Trieste was to get a room and then go on a mission to find the tiny little trattoria that impressed us so much all those years ago. Alas, it was not to be. Every last hotel room in the city was booked out because of a G20 summit. Totally gutted, we did a lap of Piazza dell’Unità d’Italia, took a picture with James Joyce and headed to the station!

Now, in a lot of nice eateries you would be offered a little grappa & espresso at the end of the meal. And that is exactly how we treated ourselves.

The first train out of Trieste happened to be leaving for none other than… Venice. An absolute no-brainer! We had our choice of rooms in Mestre and a well-deserved rest day to explore off-the-beaten track corners of Venice and the colourful outlying island of Burano.

Then, all that was left was a day of train hopping via Milano, Lugano and Zurich home to St Gallen.

Here is the “Dessert”- video

Conclusion: Via Dinarica is a trip we can highly recommend, but perhaps try to avoid July and August. It really does get too hot in too many places, and even in the mountains, temperatures can easily top 30°C.

To stock up on supplies, shops and bakeries were never far away. Evening meals tended to be on the meaty side but there were vegetarian options too. As we approached the coast, we had the full range of delicious seafood dishes. Portion sizes had hungry cyclists in mind and as a result we didn’t manage to taste desserts all that often. Main courses cost between 6 and 12 euros, increasing in price as we ventured north.

Campgrounds cost between 10 and 20 euros a night; double rooms ranged from 11-70 euros, depending on their proximity to the coast.

People are incredibly friendly and helpful in this region. Cars stopped regularly to check that everything was OK. We were given bread, cakes, fruit and drinks en route and invited for coffees and drinks all the time. Locals went way beyond their call of duty to find us accommodation and showed a genuine interest in our trip. Drivers were generally accommodating and encouraging, and there was no need to lock the bikes, even in towns.

On this positive note, we can assure you that our strenuous a-la-carte gander was well worth every drop of sweat and no doubt another plan for a trip in this beautiful region will soon be hatched. We’re still mad about this wonderful corner of Europe.